How common are cardiovascular problems after COVID? : Shots

Eleanore Beatty March 6, 2022 Article

Robi Tamargo was hospitalized at MT Sinai’s Beth Israel Hospital in New York City because of serious cardiac symptoms.

Robi Tamargo

hide caption

toggle caption

Robi Tamargo

Robi Tamargo was hospitalized at MT Sinai’s Beth Israel Hospital in New York City because of serious cardiac symptoms.

Robi Tamargo

Robi Tamargo never worried much about her heart.

The 61-year-old had started running competitively in middle school, played Division 1 sports in college and kept up her exercise routine throughout her life, working out regularly at her local gym before work.

But that changed in the spring of 2020 — when she got COVID.

Tamarago, a clinical psychologist who used to serve in the Navy, discovered a patient of hers was infected. Soon she was also sick, and it got bad quickly.

She woke up one morning in early May to discover the left side of her face was numb. At the hospital, doctors found a blood clot in her brain and were able to treat it quickly enough to prevent her from experiencing a more serious stroke.

Back home, she weathered the initial illness without need for further hospitalization, but never actually bounced back to her former health. Instead, new ailments emerged as the weeks went by. She couldn’t sleep. She had painful inflammation in the lining of her lungs. Then, three months later, her heart problems started.

“It was like my heart was coming out of my chest,” Tamargo remembers. “I spent 10 hours in the emergency room with them trying to chemically convert my heart back to a normal rhythm.”

Tamargo had developed atrial fibrillation, a common type of heart arrhythmia that leads to an irregular, sometimes rapid heart beat. It wouldn’t be the last time that her heart would send her to the hospital, though.

Robi Tamargo wears a smart watch to monitor her heart rate and other vital signs since she has had cardiac complications due to COVID-19. She has atrial fibrillation, a common type of heart arrhythmia that leads to an irregular, sometimes rapid heart beat.

Robi Tamargo

hide caption

toggle caption

Robi Tamargo

Robi Tamargo wears a smart watch to monitor her heart rate and other vital signs since she has had cardiac complications due to COVID-19. She has atrial fibrillation, a common type of heart arrhythmia that leads to an irregular, sometimes rapid heart beat.

Robi Tamargo

Last year, about a year after first contracting COVID-19, she nearly collapsed while walking up a small hill in New York City, where she’d moved temporarily to seek out specialized treatment for long COVID. “I basically had to squat down on my heels in Manhattan because I couldn’t breathe.” Her phone started ringing. It was someone from the cardiac monitoring company, which had been keeping tabs on Tamargo. “And she said, ‘you need to go to the hospital,'” Tamargo says.

Tamargo’s personal heart troubles reflect an alarming pattern among some people who’ve had COVID-19: new research shows a significant increase in the risk of heart disease and serious cardiovascular problems up to a year after the initial illness.

The massive study, published in Nature Medicine last month, analyzed electronic health records of more than 150,000 patients at the VA who were infected in the first year of the pandemic and compared their rates of cardiovascular problems to millions of other VA patients who were never infected. The study looked at a range of different medical conditions — from stroke and heart attack to arrhythmias and inflammation of the heart muscles.

Overall, the study found the incidence of serious cardiac and cardiovascular problems was 4{a78e43caf781a4748142ac77894e52b42fd2247cba0219deedaee5032d61bfc9} higher in the 12 months after people were diagnosed with COVID-19 compared to those who were not infected.

“Even though 4{a78e43caf781a4748142ac77894e52b42fd2247cba0219deedaee5032d61bfc9} is a single-digit number and it may seem small to some people, but you have to multiply that by the huge number of people in the U.S. and many, many more around the world who experienced COVID-19 infections,” says the study’s lead author Dr. Ziyad Al-Aly, director of clinical epidemiology at the Veterans Affairs St. Louis Health Care System. “This is really going to create a generation of people with heart problems.”

The increased risk was observed even among those who had a mild case of COVID-19. It also wasn’t limited to people with pre-existing risks for heart disease or other cardiovascular problems. “We found it in young people, people who were previously athletic, people who never smoked, people who were not obese, people who never had diabetes,” says Al-Aly.

The study’s strengths include its huge size and rigorous statistical analysis with multiple controls, says Dr. Larisa Tereshchenko, a cardiologist and biostatistician at the Cleveland Clinic.

“I trust the findings. I think it’s real,” says Tereshchenko, who has conducted her own study on the cardiovascular risks after a coronavirus infection, albeit with a much smaller sample size.

Specifically, Al-Aly’s study found that COVID-19 patients were about 63{a78e43caf781a4748142ac77894e52b42fd2247cba0219deedaee5032d61bfc9} more likely to have a heart attack and 52{a78e43caf781a4748142ac77894e52b42fd2247cba0219deedaee5032d61bfc9} more likely to have a stroke, compared to the control groups.

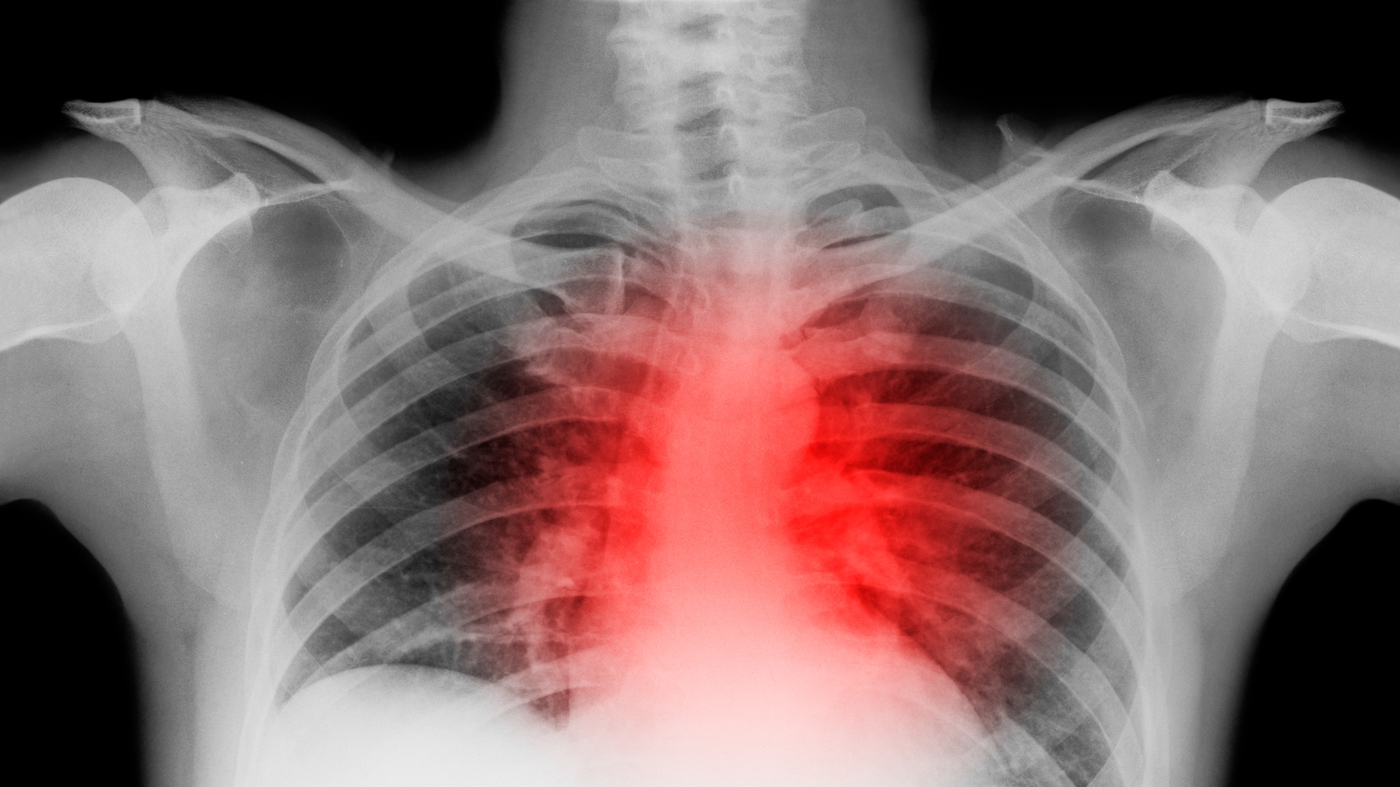

A large study found the incidence of cardiac and other serious cardiovascular problems was 4{a78e43caf781a4748142ac77894e52b42fd2247cba0219deedaee5032d61bfc9} higher in the 12 months after people were diagnosed with COVID-19 compared to those who were not infected.

Peter Dazeley/Getty Images

hide caption

toggle caption

Peter Dazeley/Getty Images

A large study found the incidence of cardiac and other serious cardiovascular problems was 4{a78e43caf781a4748142ac77894e52b42fd2247cba0219deedaee5032d61bfc9} higher in the 12 months after people were diagnosed with COVID-19 compared to those who were not infected.

Peter Dazeley/Getty Images

Questions about how findings apply to mild and breakthrough cases

Despite its size, the study has some limitations: it was done retrospectively and draws on a majority white and male patient population. And because the data was collected between March 2020 and January 2021, it’s unclear how relevant the findings are to the millions of people who’ve been infected after being vaccinated, says Dr. Betty Raman, a cardiologist with the Radcliffe Department of Medicine at the University of Oxford.

“Things are dramatically different in terms of the way the body is handling the infection,” says Raman. “I think a lot of these findings are difficult to extrapolate to the vaccinated population and to the more recent variants.”

Raman thinks it’s unlikely that the risk of cardiovascular events will prove to be as high for people who’ve been vaccinated and get a breakthrough case, in part because those cases tend to be milder.

Raman points out that in the study, severity of disease strongly predicts the likelihood of serious heart or cardiovascular problems.

Patients who’d been hospitalized with COVID had about twice the rate of major adverse cardiovascular events in the 12 months following infection as those who had milder COVID and weren’t hospitalized, the study found. Rates were highest for those who had to be treated in the ICU.

Disease severity “is absolutely critical in driving that increased risk,” Raman says.

Nevertheless, the findings have reverberated among cardiologists who are treating patients plagued with persistent symptoms and medical problems in the wake of a coronavirus infection.

“I think this was a wakeup call to us,” says Dr. Harlan Krumholz, a cardiologist at the Yale School of Medicine, who’s also involved with long COVID research.

However, Krumholz stresses the study should not be cause for panic. The absolute risk remains quite low for most people who get infected with the coronavirus. The study found that, among those who got sick but were not hospitalized, 56 out of every 1,000 had a major adverse cardiovascular event — namely heart attack and stroke — in the 12 months following an infection.

“It’s not like, ‘Oh my gosh, everyone got COVID and the next thing you know, they all had heart attacks — that’s not it,” Krumholz says.

Indeed, Dr. Sean Pinney has patients who’ve seen the study’s topline results and have come to him concerned about their long-term health.

“We need to prepare ourselves to screen patients for this increased burden of cardiovascular disease,” says Pinney, co-director of the Heart and Vascular Center at the University of Chicago. “But it’s important to look at this from the other viewpoint: what’s an individual patient’s risk? And this study doesn’t tell us that.”

Worries about long-term cardiovascular damage

The study also can’t explain why COVID can have this effect on some people’s cardiovascular systems, but scientists have been trying to piece this together since the early days of the pandemic. Scientists also don’t know how long-term the cardiovascular effects of COVID may turn out to be.

It’s clear that COVID-19 can trigger a tremendous amount of inflammation and that can wreak havoc on the vascular system, leading to dangerous blood clots in the lungs and other parts of the body. And scientists have shown that the virus can infect different types of heart cells in the lab and thereby interfere with heart muscle contraction.

Doctors sometimes see myocardial damage, or inflammation of parts of the heart muscles, in COVID patients, says Dr. Peter Libby, a cardiologist at Harvard Medical School and Brigham & Women’s Hospital. “The question is how much of it is reversible and how much of it is enduring and will be reaping in the coming decades?” he says. “It doesn’t take a very big scar to predispose you to have arrhythmias.”

Dysfunction within the delicate lining of blood vessels, made up of what are called endothelial cells, is also thought to play a major role in the progression of COVID-19 and could also have lasting consequences for cardiovascular health.

“We’re laying the groundwork for blood clotting problems and problems with the ability to regulate the circulation appropriately.” Libby says. “The small vessels that really control the circulation in the heart and also in the periphery are dependent on good endothelial function.”

Still, researchers point out that it’s possible some of the VA study’s findings are not just specific to coronavirus, but instead represent possible long term effects of a viral infection in general. “For many infections, you can have pro-inflammatory changes, the inflammation in the body can persist,” says Krumholz. “We know from a large number of studies that inflammation can be associated with heart disease.”

He points to studies dating from before the pandemic that have found patients hospitalized for pneumonia are at increased risk of long term cardiovascular disease. “But the fact that this might not be specific to COVID shouldn’t give us much comfort,” Krumholz says, “because there are a lot of people who’ve been infected, so the denominator is quite large.”

You may also like

Archives

- December 2024

- November 2024

- September 2024

- August 2024

- July 2024

- February 2024

- January 2024

- December 2023

- November 2023

- October 2023

- September 2023

- August 2023

- July 2023

- June 2023

- May 2023

- April 2023

- March 2023

- February 2023

- January 2023

- December 2022

- November 2022

- October 2022

- September 2022

- August 2022

- July 2022

- June 2022

- May 2022

- April 2022

- March 2022

- February 2022

- January 2022

- December 2021

- November 2021

- October 2021

Calendar

| M | T | W | T | F | S | S |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

| 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 |

| 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 |

| 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 | 27 |

| 28 | 29 | 30 | 31 | |||