The FBI is promising to make sure employees who have symptoms consistent with Havana Syndrome get access to medical care after a former agent suffering almost daily headaches was rebuffed when he sought testing and treatment, according to documents obtained by NBC News.

In an email last month, an FBI official told a former agent who had reported possible brain injury symptoms that “unfortunately, the FBI is not authorized to give any medical advice and there are not any medical programs in place for current and/or retired employees.” The agent began suffering migraines and dizziness about a decade ago after a stint overseas in a country near Russia.

Asked about the assertion, the FBI responded in a statement that confirmed the email, saying it was “one part of a larger exchange taken out of context and does not reflect the FBI’s commitment to supporting its personnel, both current and former.”

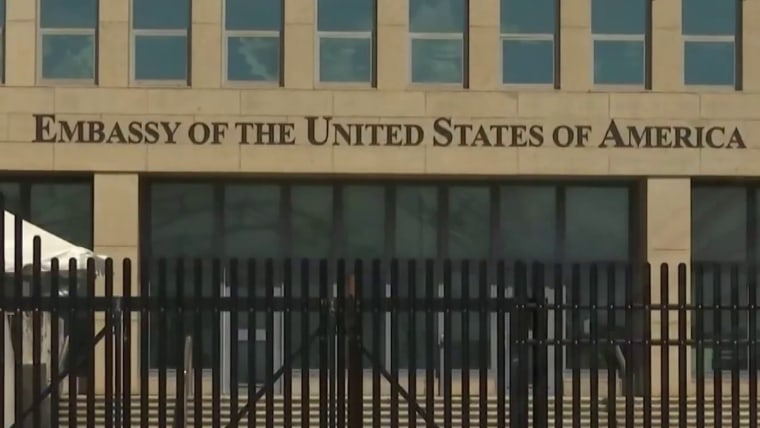

The statement amounted to the FBI’s first formal acknowledgment that some of its current or former employees could have symptoms of Havana Syndrome, which got its name after a group of diplomats and CIA officers reported symptoms in 2016 at the U.S. Embassy in Cuba. Although the bureau did not confirm or deny the existence of FBI cases, NBC News has previously reported that several FBI personnel have reported possible symptoms, including some who had been posted to Vienna.

The statement said that while the FBI “does not have the authority to provide direct medical treatment, we now have a process to guide current and former employees to the interagency medical treatment and evaluation options that are available to them.”

The statement did not say when the FBI implemented the policy; the language of the October email suggests that it was not in place last month.

The statement added that the issue of “Anomalous Health Incidents,” as the U.S. government calls the mysterious set of symptoms afflicting as many as 200 current or former government employees, “is a top priority for the FBI, as the protection, health and well-being of our employees and colleagues across the federal government is paramount.”

The FBI, the statement said, “has messaged its workforce on how to respond if they experience an AHI, how to report an incident, and where they can receive medical evaluations for symptoms or persistent effects.”

Over the past year, U.S. government agencies have encouraged employees to report any possible symptoms, and some who have come forward have health effects that began occurring before the 2016 Havana incidents. Several U.S. officials said not all of those who have come forward fit the profile of the Havana cohort. At the same time, brain injuries can be difficult to diagnose, so officials have encouraged anyone who suspects something wrong to come forward.

The former FBI agent was posted to an embassy that came under a suspected Russian electronic jamming operation that disrupted communications, he said, asking not to be identified because he was concerned that it could affect how the FBI handles his case. He began experiencing symptoms shortly afterward, and he has lived the past decade with almost daily headaches, dizziness and fatigue.

The National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine said in a report last year that some of the observed brain injuries were consistent with the effects of directed microwave energy, which the report said Russia has long studied.

A team of medical and scientific experts who studied the symptoms of as many as 40 State Department and other government employees concluded that nothing like them had previously been documented in medical literature, the National Academies of Sciences report said. Many reported hearing a loud sound and feeling pressure in their heads and then experiencing dizziness, unsteady gait and visual disturbances. Many suffered long-standing debilitating effects.

NBC News reported in 2018 that U.S. intelligence officials considered Russia a leading suspect in what some of them assess to have been deliberate attacks on diplomats and CIA officers overseas. But in the nearly three years since then, the spy agencies have not uncovered enough evidence to pinpoint the cause or the culprit of the health incidents. U.S. officials cannot say for sure that they were intentional attacks or even that they were the result of human activity.

While some intelligence officials strongly suspect Russia, the longer intelligence agencies investigate without finding compelling evidence, the more questions are raised about that conclusion. Experts say it is hard to imagine that a secret Russian program to harm U.S. spies and diplomats could go completely undetected by the $80 billion U.S. intelligence apparatus, which is regularly hacking Russian communications, conducting surveillance of Russian officers and recruiting Russians to spy for the U.S.

Russia has consistently denied any culpability.

At a public forum in September, Deputy CIA Director David Cohen suggested that the agency has made some progress, but not enough.

“In terms of have we gotten closer? I think the answer is yes — but not close enough to make the analytic judgment that people are waiting for,” he said.