Synthetic Media: How deepfakes could soon change our world – 60 Minutes

Eleanore Beatty November 21, 2021 ArticleYou may never have heard the term “synthetic media”— more commonly known as “deepfakes”— but our military, law enforcement and intelligence agencies certainly have. They are hyper-realistic video and audio recordings that use artificial intelligence and “deep” learning to create “fake” content or “deepfakes.” The U.S. government has grown increasingly concerned about their potential to be used to spread disinformation and commit crimes. That’s because the creators of deepfakes have the power to make people say or do anything, at least on our screens. Most Americans have no idea how far the technology has come in just the last four years or the danger, disruption and opportunities that come with it.

Deepfake Tom Cruise: You know I do all my own stunts, obviously. I also do my own music.

Chris Ume/Metaphysic

This is not Tom Cruise. It’s one of a series of hyper-realistic deepfakes of the movie star that began appearing on the video-sharing app TikTok earlier this year.

Deepfake Tom Cruise: Hey, what’s up TikTok?

For days people wondered if they were real, and if not, who had created them.

Deepfake Tom Cruise: It’s important.

Finally, a modest, 32-year-old Belgian visual effects artist named Chris Umé, stepped forward to claim credit.

Chris Umé: We believed as long as we’re making clear this is a parody, we’re not doing anything to harm his image. But after a few videos, we realized like, this is blowing up; we’re getting millions and millions and millions of views.

Umé says his work is made easier because he teamed up with a Tom Cruise impersonator whose voice, gestures and hair are nearly identical to the real McCoy. Umé only deepfakes Cruise’s face and stitches that onto the real video and sound of the impersonator.

Deepfake Tom Cruise: That’s where the magic happens.

For technophiles, DeepTomCruise was a tipping point for deepfakes.

Deepfake Tom Cruise: Still got it.

Bill Whitaker: How do you make this so seamless?

Chris Umé: It begins with training a deepfake model, of course. I have all the face angles of Tom Cruise, all the expressions, all the emotions. It takes time to create a really good deepfake model.

Bill Whitaker: What do you mean “training the model?” How do you train your computer?

Chris Umé: “Training” means it’s going to analyze all the images of Tom Cruise, all his expressions, compared to my impersonator. So the computer’s gonna teach itself: When my impersonator is smiling, I’m gonna recreate Tom Cruise smiling, and that’s, that’s how you “train” it.

Chris Ume/Metaphysic

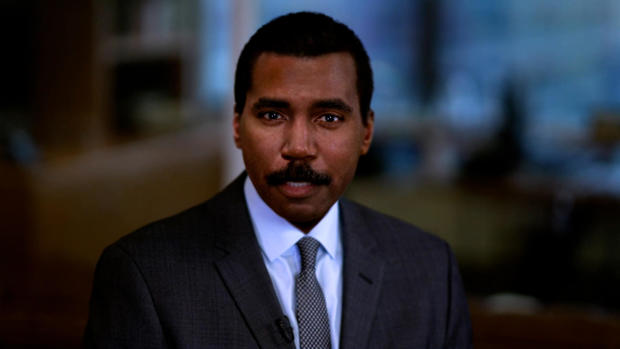

Using video from the CBS News archives, Chris Umé was able to train his computer to learn every aspect of my face, and wipe away the decades. This is how I looked 30 years ago. He can even remove my mustache. The possibilities are endless and a little frightening.

Chris Umé: I see a lot of mistakes in my work. But I don’t mind it, actually, because I don’t want to fool people. I just want to show them what’s possible.

Bill Whitaker: You don’t want to fool people.

Chris Umé: No. I want to entertain people, I want to raise awareness, and I want

and I want to show where it’s all going.

Nina Schick: It is without a doubt one of the most important revolutions in the future of human communication and perception. I would say it’s analogous to the birth of the internet.

Political scientist and technology consultant Nina Schick wrote one of the first books on deepfakes. She first came across them four years ago when she was advising European politicians on Russia’s use of disinformation and social media to interfere in democratic elections.

Bill Whitaker: What was your reaction when you first realized this was possible and was going on?

Nina Schick: Well, given that I was coming at it from the perspective of disinformation and manipulation in the context of elections, the fact that AI can now be used to make images and video that are fake, that look hyper realistic. I thought, well, from a disinformation perspective, this is a game-changer.

So far, there’s no evidence deepfakes have “changed the game” in a U.S. election, but earlier this year the FBI put out a notification warning that “Russian [and] Chinese… actors are using synthetic profile images” — creating deepfake journalists and media personalities to spread anti-American propaganda on social media.

The U.S. military, law enforcement and intelligence agencies have kept a wary eye on deepfakes for years. At a 2019 hearing, Senator Ben Sasse of Nebraska asked if the U.S. is prepared for the onslaught of disinformation, fakery and fraud.

Ben Sasse: When you think about the catastrophic potential to public trust and to markets that could come from deepfake attacks, are we organized in a way that we could possibly respond fast enough?

Dan Coats: We clearly need to be more agile. It poses a major threat to the United States and something that the intelligence community needs to be restructured to address.

Since then, technology has continued moving at an exponential pace while U.S. policy has not. Efforts by the government and big tech to detect synthetic media are competing with a community of “deepfake artists” who share their latest creations and techniques online.

Like the internet, the first place deepfake technology took off was in pornography. The sad fact is the majority of deepfakes today consist of women’s faces, mostly celebrities, superimposed onto pornographic videos.

Nina Schick: The first use case in pornography is just a harbinger of how deepfakes can be used maliciously in many different contexts, which are now starting to arise.

Bill Whitaker: And they’re getting better all the time?

Nina Schick: Yes. The incredible thing about deepfakes and synthetic media is the pace of acceleration when it comes to the technology. And by five to seven years, we are basically looking at a trajectory where any single creator, so a YouTuber, a TikToker, will be able to create the same level of visual effects that is only accessible to the most well-resourced Hollywood studio today.

Chris Ume/Metaphysic

The technology behind deepfakes is artificial intelligence, which mimics the way humans learn. In 2014, researchers for the first time used computers to create realistic-looking faces using something called “generative adversarial networks,” or GANs.

Nina Schick: So you set up an adversarial game where you have two AIs combating each other to try and create the best fake synthetic content. And as these two networks combat each other, one trying to generate the best image, the other trying to detect where it could be better, you basically end up with an output that is increasingly improving all the time.

Schick says the power of generative adversarial networks is on full display at a website called “ThisPersonDoesNotExist.com”

Nina Schick: Every time you refresh the page, there’s a new image of a person who does not exist.

Each is a one-of-a-kind, entirely AI-generated image of a human being who never has, and never will, walk this Earth.

Nina Schick: You can see every pore on their face. You can see every hair on their head. But now imagine that technology being expanded out not only to human faces, in still images, but also to video, to audio synthesis of people’s voices and that’s really where we’re heading right now.

Bill Whitaker: This is mind-blowing.

Nina Schick: Yes. [Laughs]

Bill Whitaker: What’s the positive side of this?

Nina Schick: The technology itself is neutral. So just as bad actors are, without a doubt, going to be using deepfakes, it is also going to be used by good actors. So first of all, I would say that there’s a very compelling case to be made for the commercial use of deepfakes.

Victor Riparbelli is CEO and co-founder of Synthesia, based in London, one of dozens of companies using deepfake technology to transform video and audio productions.

Victor Riparbelli: The way Synthesia works is that we’ve essentially replaced cameras with code, and once you’re working with software, we do a lotta things that you wouldn’t be able to do with a normal camera. We’re still very early. But this is gonna be a fundamental change in how we create media.

Synthesia makes and sells “digital avatars,” using the faces of paid actors to deliver personalized messages in 64 languages… and allows corporate CEOs to address employees overseas.

Snoop Dogg: Did somebody say, Just Eat?

Synthesia has also helped entertainers like Snoop Dogg go forth and multiply. This elaborate TV commercial for European food delivery service Just Eat cost a fortune.

Snoop Dogg: J-U-S-T-E-A-T-…

Victor Riparbelli: Just Eat has a subsidiary in Australia, which is called Menulog. So what we did with our technology was we switched out the word Just Eat for Menulog.

Snoop Dogg: M-E-N-U-L-O-G… Did somebody say, “MenuLog?”

Victor Riparbelli: And all of a sudden they had a localized version for the Australian market without Snoop Dogg having to do anything.

Bill Whitaker: So he makes twice the money, huh?

Victor Riparbelli: Yeah.

All it took was eight minutes of me reading a script on camera for Synthesia to create my synthetic talking head, complete with my gestures, head and mouth movements. Another company, Descript, used AI to create a synthetic version of my voice, with my cadence, tenor and syncopation.

Deepfake Bill Whitaker: This is the result. The words you’re hearing were never spoken by the real Bill into a microphone or to a camera. He merely typed the words into a computer and they come out of my mouth.

It may look and sound a little rough around the edges right now, but as the technology improves, the possibilities of spinning words and images out of thin air are endless.

Deepfake Bill Whitaker: I’m Bill Whitaker. I’m Bill Whitaker. I’m Bill Whitaker.

Bill Whitaker: Wow. And the head, the eyebrows, the mouth, the way it moves.

Victor Riparbelli: It’s all synthetic.

Bill Whitaker: I could be lounging at the beach. And say, “Folks– you know, I’m not gonna come in today. But you can use my avatar to do the work.”

Victor Riparbelli: Maybe in a few years.

Bill Whitaker: Don’t tell me that. I’d be tempted.

Tom Graham: I think it will have a big impact.

The rapid advances in synthetic media have caused a virtual gold rush. Tom Graham, a London-based lawyer who made his fortune in cryptocurrency, recently started a company called Metaphysic with none other than Chris Umé, creator of DeepTomCruise. Their goal: develop software to allow anyone to create hollywood-caliber movies without lights, cameras, or even actors.

Tom Graham: As the hardware scales and as the models become more efficient, we can scale up the size of that model to be an entire Tom Cruise; body, movement and everything.

Bill Whitaker: Well, talk about disruptive. I mean, are you gonna put actors out of jobs?

Tom Graham: I think it is a great thing if you’re a well-known actor today because you may be able to let somebody collect data for you to create a version of yourself in the future where you could be acting in movies after you have deceased. Or you could be the director, directing your younger self in a movie or something like that.

If you are wondering how all of this is legal, most deepfakes are considered protected free speech. Attempts at legislation are all over the map. In New York, commercial use of a performer’s synthetic likeness without consent is banned for 40 years after their death. California and Texas prohibit deceptive political deepfakes in the lead-up to an election.

Nina Schick: There are so many ethical, philosophical gray zones here that we really need to think about.

Bill Whitaker: So how do we as a society grapple with this?

Nina Schick: Just understanding what’s going on. Because a lot of people still don’t know what a deepfake is, what synthetic media is, that this is now possible. The counter to that is, how do we inoculate ourselves and understand that this kind of content is coming and exists without being completely cynical? Right? How do we do it without losing trust in all authentic media?

That’s going to require all of us to figure out how to maneuver in a world where seeing is not always believing.

Produced by Graham Messick and Jack Weingart. Broadcast associate, Emilio Almonte. Edited by Richard Buddenhagen.

You may also like

Archives

- December 2024

- November 2024

- September 2024

- August 2024

- July 2024

- February 2024

- January 2024

- December 2023

- November 2023

- October 2023

- September 2023

- August 2023

- July 2023

- June 2023

- May 2023

- April 2023

- March 2023

- February 2023

- January 2023

- December 2022

- November 2022

- October 2022

- September 2022

- August 2022

- July 2022

- June 2022

- May 2022

- April 2022

- March 2022

- February 2022

- January 2022

- December 2021

- November 2021

- October 2021

Calendar

| M | T | W | T | F | S | S |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

| 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 |

| 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 |

| 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 | 27 |

| 28 | 29 | 30 | 31 | |||